What's the Deal with Organics?

Organics. What's the deal with them, anyways? They've obviously caused quite a stir lately, what with all this fear of genetic engineering (aka GMOs). The general public perception is that organic crops and livestock must somehow be better because they're more expensive and come in a prettier package. However, like any food product, there are both pros and cons. Since we here at The Truth About Agriculture only care about cold, hard facts, I'll help you sort through the benefits and drawbacks so that you get all the truth, and none of the pseudoscience. I realize that to some of you who are reading this, it may come across as anti-organic. Not so. As I said, there are both pros and cons. You as a consumer deserve ALL the facts so that you can make an informed decision about what type of food you eat. If you refuse to eat anything other than organic after reading this, good for you! At least you made an informed decision! If you can only buy conventional because organic is too expensive, that's completely okay as well! You don't have to feel guilty, because conventionally grown products are just as good. So without further ado, the pros and cons of organic food.

Pros:

I confess that when I was doing research for this post, I came across a lot of faulty articles that made many false claims about the pros of organic foods. I also came across a lot of "pros" of organic foods that are definitely pros, but are not unique to organic food. So I'll list them here, and explain the facts in detail so you have a better understanding of what each fact actually means.

1.) Processed organic foods do not contain trans fat.

There's no question that trans (aka hydrogenated) fat is bad. It's pretty much common knowledge at this point. However, not many people know WHY they're bad. I'll explain. There are two main naturally-occurring types of fats consumed in the diet of a human: saturated and unsaturated. Unsaturated fats contain double bonds between carbon atoms, preventing them from becoming "saturated" with hydrogens. As a result of these double bonds, the fat molecules (called lipids) can't hold together well enough to form a solid. Because of this, unsaturated fats (we'll give them the acronym UFAs) are usually liquids. We find these in plant oils such as canola, avocado, and olive oils. These double-bonded fats are the so-called "good" fats we hear about all the time (I would argue that saturated fats can also be good for you as long as you don't eat too many of them, but that's a story for another day). According to Harvard Medical School, UFAs can lower your levels of "bad" LDL cholesterol and also your triglycerides. This is also the same category of fats as Omega-3 and Omega-6. You need to eat these fats to survive because you can't make them yourself.

The second type of naturally-occurring fat is saturated fat. We'll abbreviate them to "SFAs." SFA lipids do not contain double bonds between carbon atoms, allowing them to become "saturated" with hydrogen atoms. Because of this, they stick together into solids more readily than UFAs do. SFAs are found in mainly animal products such as meat, milk, and eggs, although there are plant sources as well, such as coconut oil. Ever wondered why it's the only plant oil that's solid at room temperature? Now you know. You're welcome. SFAs are considered a "bad" fat by some because when consumed to excess, they can raise your cholesterol count and increase the presence of LDL cholesterol. However, they serve important biological functions as well. SFAs are responsible for making sure your cell membranes don't fly apart. A delicate balance of UFAs and SFAs is responsible for making sure nutrients can get in and out of your cells. It's also stored in adipose cells for use as nutrition during times of scarce food, or as insulation from the cold and cushioning from impacts around the gastrointestinal organs (1).

But what about trans fat? Recall that plant oils are liquids because they're unsaturated. If that were true, however, how would we get products like crisco and margarine that are made from plants, but are solid? There is a process to artificially break the double bonds in plant oils by heating them up with a catalyst like palladium in order to saturate them fully, since saturated fats are solids. However, this process (called "hydrogenation") changes the basic chemical structure of the fat, causing its chemical structure to look completely different than it did before. We call these twisted lipids "trans" fats (1). They're found in fried foods and all the yummy stuff, like fast food burgers, doughnuts, and processed cookies and pastries. They taste really, really good, but in all honesty, if you have to boil palladium in hot vegetable oil and hydrogen in order to get a food item, do you really think you should be eating it? Just look at what palladium did to Iron Man.

| "Palladium in the chest. Painful way to die" -Crazy Russian Guy I kid of course. This is fiction. Sticking a chunk of metal in your chest isn't always toxic, especially if that chunk of metal is a pacemaker. |

Kind of prophetic, huh? You get trans fat by boiling palladium in oil and hydrogen, and it gives you heart disease. Sticking a massive chunk of it directly on top of his heart was killing Iron Man. Once again, I'm just making a joke. Science fiction movies are extremely inaccurate, although palladium really is a carcinogen (2). But there is good news! As of 2018, trans fats will be banned from the American food supply, as per FDA regulations (3)! So the lack of trans fats in processed organics now is definitely a pro. In the future, however, it will be no different than what you'd find in a conventional product. Until then, however, it remains a very good argument for eating organic products. To be fair, however, you can check the nutrition label of conventional foods. While not currently prohibited from adding trans fat, most regular products don't contain it either. You can tell for sure by reading the label.

2.) If it's that important to you, organic animals get access to the outdoors.

This is what I like to call a "quasi pro." Personally, as someone who has extensively studied conventional animal production systems, I don't think it makes much difference whether they're raised inside or outside. Inside, animals are protected from the elements, don't have to worry about predators, and are less likely to get sick from air-born pathogens. Which sucks for organic animals, because synthetic antibiotics aren't allowed in organic agriculture. Pretty much the only antibiotic you can give an organic animal if you want to maintain its organic status is penicillin (4). This is because it's a natural antibiotic that's derived from mold.

In addition, a certain percentage of the diet of organic ruminant animals like cattle and sheep must be grass. This wouldn't be such a bad thing, except that for animals like dairy cattle, lots of grass in their diet isn't really a good thing. Dairy cattle have complex nutrition requirements that involve supplementing certain amino acids, calcium, and energy-rich concentrates to help them maintain a healthy weight and a strong body. They do need roughages, but not to the degree some people assume. Lots of grass in the diet can affect the quality of meats like beef, which aren't necessarily positive, as I explain here. Does being outside actually HARM the animals? Well, no, but it isn't necessarily better for them. Other USDA standards like shade, shelter, clean bedding, and clean water are priorities for conventional farmers, too. These practices aren't required of conventional farmers, but taking care of livestock properly helps them thrive and drives up profit margins. Happy livestock mean more meat, milk, eggs, fiber, etc., and therefore more money for farmers. They have families to provide for too, and mistreating livestock at a loss to their business doesn't make much sense when you look at it from that perspective. So if you think livestock should be raised outside, this is a pro for you. If you don't really care where they're raised, as long as they're treated well, you can rest easy buying conventional.

3.) No SYNTHETIC pesticides

Many organic companies advertise for their products with labels that look like this:

I respectfully call B.S. Specifically because organic farming DOES use pesticides. Just not synthetic ones (5). Commonly used organic pesticides include copper sulfate, elemental sulfur, borax, and borates (6). Some organic pesticides are even more toxic than synthetic ones, especially copper sulfate, which is often applied at a higher concentration than synthetic pesticides like glyphosphate.

Story time! Once upon a time, there was a bacterium called Bt (short for Bacillus thuringiensis) that was the most widely used pesticide used in organic farming. Bt accounted for 90% of the organic pest control market. Scientists took note. Using their magic, they genetically engineered a gene from this special, little bacterium called the Bt Cry protein into cotton, corn, and soy. The scientists thought that the people of their land would be pleased with the new crops, which did not need to be sprayed with pesticides, thereby reducing the amount that accumulated in runoff and in the soil. The scientists were very pleased with their work, until one day the big, bad activists rolled into town. They did not understand science and did not understand that they were already eating Bt on their organic crops. They convinced the entire land that Bt crops were somehow poisonous. Then, they huffed and they puffed and they blew those beautiful Bt crops to smithereens.

Did you like my fairy tale? Unfortunately, this actually happened. Despite Bt's widespread direct application to organic crops, anti-GMO activists are still convinced that crops with the Bt Cry protein engineered into them are toxic, even though they decrease pesticide use, and even though Bt bacteria can be sprayed onto organic crops, and are the most widely used organic pesticide (6). Does anyone else see the irony in that?

So yeah. If you're opposed to synthetic pesticides, buy organic. Just be aware that organic crops use pesticides too. And in the interest of fairness, I would like to point out that pesticide use on crops isn't necessarily bad. It's the dose that makes the poison. You're a lot bigger than a bole weevil. It takes much, much smaller amounts of poison to kill a bug than it does to even cause an adverse reaction in a human. I'll just leave this picture here for your consideration:

|

1.) They cost more. A lot more.

Organic crops cost more for several reasons. First, organic farmers don't receive subsidies from the federal government. What's a subsidy? Basically, the government gives conventional farmers money so that they can keep their prices low. This is advantageous because it ensures a cost-effective, abundant food supply. When subsidies are denied to organic farmers, however, they must raise prices because not as many of their costs are covered by the government, and they must cover them with profit margins.

The second reason organics are more expensive is that organic farms are usually smaller than their conventional counterparts. In 2011, just .26% of U.S. farmland used to grow corn was certified organic, as per the USDA. The highest ratio of organic acreage to conventional acreage for a particular crop was that of carrots. In 2011, 14.35% of U.S. farmland used to grow carrots was certified organic. What about animals? The highest percentage was that of dairy cattle, with only 2.78% of all U.S. dairy cattle (not counting replacement heifers) being certified organic. You can find those numbers, plus a ton more here. What do these small percentages mean? It means scarcity will cause an increase in demand, economically speaking. Consider this demand curve:

|

| We'll start out with a demand curve of D1 and supply curve S |

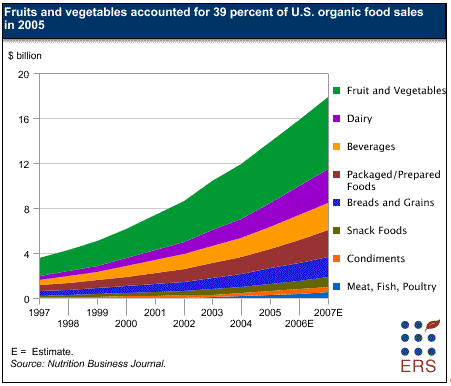

Suppose we start off with a price of P1 for one bunch of organic celery and a quantity demanded of Q1. The trend towards organic food in the past years has only increased, as seen on the graph below:

|

2.) Organic fruits and veggies spoil more quickly.

Yup. There's a reason organic bananas at the supermarket always look like they're about to go rotten. They haven't been irradiated. Before you start screaming about how harmful radiation is, what do you think happens when you put food in the microwave? You irradiate it with microwaves. The USDA says that irradiation of food is 100% safe, and in fact makes foods like poultry safer by reducing the amount of harmful bacteria present. It doesn't make food radioactive because the radiation passes all the way through the food, and out the other side. The food never actually comes in contact with the source of radient energy. Some argue that this process destroys vital nutrients, but nutrient losses due to radiation are less than or equal to losses that occur from freezing or cooking. In other words, it's negligible. I'd say the benefits (increased shelf life) outweigh the problems (a little bit of nutrient degradation). So if you pay all that extra money for organic fruits and veggies, don't expect them to last very long.

3.) It could be contaminated with E. coli.

Synthetic fertilizers aren't allowed in organic production. So what do organic farmers fertilize their crops with instead? POOP!

Manure is a cheap, effective natural fertilizer that many organic farmers use to increase yields. However, using manure for fertilizer comes with a risk. Manure can contain contaminants like E. coli or Salmonella that come from the digesta of animals, excreted in the feces. It's not a problem as long as you cook your food or as long as you irradiate it, but organics aren't irradiated, and what if you want to eat an organic salad? There have been cases such as this one, where the FDA was forced to recall organic spinach because of Listeria contamination. I'd be willing to bet money that most buyers of organic food don't know their produce was grown in poop.

What you should take away

Numbered Sources

(6) https://www.geneticliteracyproject.org/2016/12/01/myth-busting-on-pesticides-despite-demonization-organic-farmers-widely-use-them/

I'm a full-time college student at Texas A&M University, where I'm in the process of getting my Animal Science degree, with eventual aspirations to go to law school and work as a consulting lawyer for agriculture corporations. I grew up around animals, and currently manage an operation that breeds show-quality boer goats for 4H and FFA exhibitors. My family also raises commercial cattle in south Texas.

I'm a full-time college student at Texas A&M University, where I'm in the process of getting my Animal Science degree, with eventual aspirations to go to law school and work as a consulting lawyer for agriculture corporations. I grew up around animals, and currently manage an operation that breeds show-quality boer goats for 4H and FFA exhibitors. My family also raises commercial cattle in south Texas.

Comments

Post a Comment